NOTE: I imagine the Educational Philosophy to be an evolving document that shifts based on teaching experience, pedagogical tinkering, and professional research.

Every student is a relationship a teacher must create and nurture. Once students are safe and healthy, stimulating and sustaining curiosity are essential to each lesson plan. I believe students energized by passionate and curious teachers open themselves to unexpected learning.

I develop in students an awareness of the type of reader, writer, thinker, and speaker they are becoming and give them opportunities to practice each in a safe environment where missteps are required and mastery is a goal. Without the partnership of parents and guardians, learning gets siloed as a school activity.

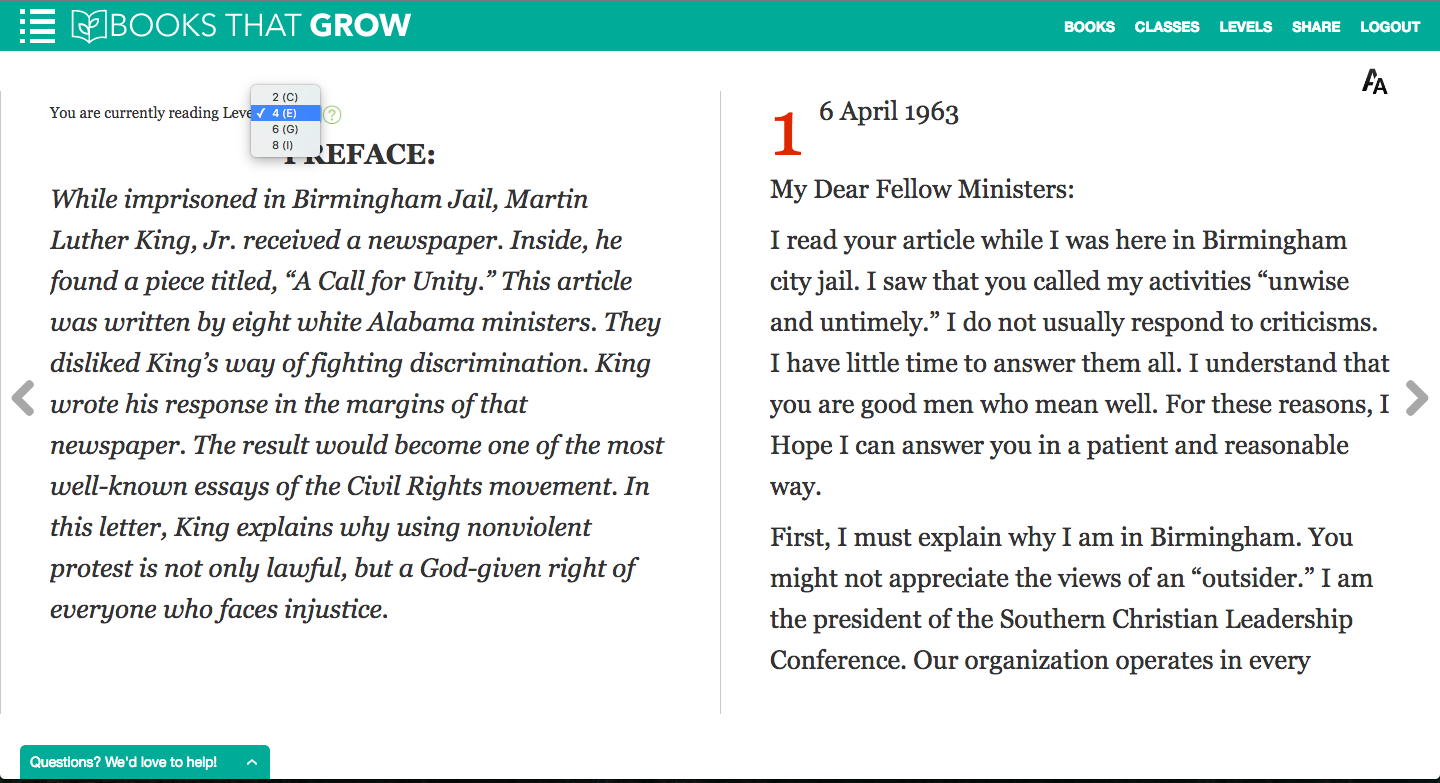

I believe in backwards design but also experimentation and improvisation. I recognize the existence of learning styles but believe students should practice learning across modalities, even those causing discomfort. I see novelty as currency, but one easily spent and necessarily saved for particular moments.

I see feedback, not judgmental grading, as a key to unlocking a student’s willingness to adapt and improve. Grading without feedback turns education into a scavenger hunt for “points.” Feedback without grades primes a student’s growth mindset.

I recognize that learning can happen in the in-between moments, when teachers least expect it and that students may learn different things despite the same lesson plan. I believe that classrooms are essential only if social learning is a stated outcome of the school. I center the student in the classroom and aim to describe their learning more than prescribe it.

I see value in emerging pedagogical trends, research-based practices, and also teaching to one’s strengths.

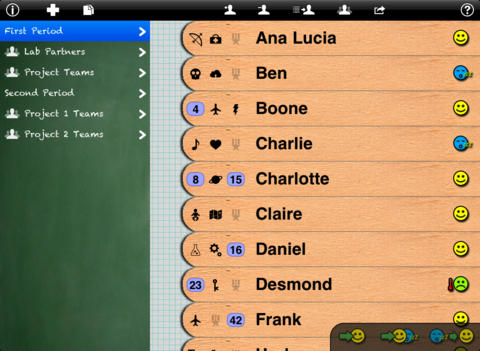

I am known for planning every minute, experimenting with educational technology, tantalizing students with my own enthusiasm for content, providing differentiated feedback, and embedding contemporary events into the curriculum in real time.

I teach, so I can learn.